Mattah/THE ROCKING STONE

The mountain is covered with countless standing, leaning, fallen, broken and imbedded tors. It has vast fields of enormous boulders and numerous perched stones and rocky outcrops, but one stone—one nowhere near the top, not on any track, not especially large or distinguished-looking—has been named and visited and photographed for centuries.

Though the first mention we have of “The Rocking Stone” seems late—1864—the writer made no claim to its discovery, implying that the Stone was a familiar. Climbers on the earliest pathway from Hobart to the Pinnacle (c1810] passed near it; and strong parties who reached the Pinnacle from the opposite side (the east) sometimes continued on to South Wellington so the Rocking Stone may have been known to the earliest excursionists.

Visited by parties from around Australia, accounts appearing in newspapers throughout the land (the first in Sydney, not Hobart) spread its fame. It had a brief Australia-wide recognition through line-drawings in national illustrated newspapers, as well as in New Zealand’s Illustrated Press in 1873.

Around the turn of the 20th century the Stone got its own postcard. In the 1910s they were hand-tinted. In the 21st century it became a stock image.

“[By the 1870s] there are photographs of ... of the Rocking Stone and other like features. If one could have a human figure lounging on said interesting feature so much the better. ”

Perched just over The Gap, on the ridge, it is a natural spot for a reststop and became a favoured picnic area.

“It was on New Year’s Day that a company of just thirteen persona were seated on the shady side of “the Rocking Stone,” engaged in disposing of that substantial kind of lunch which parties who make holiday trips to the summit of Mount Wellington are in the habit of indulging in...”

In New Year’s Day on the Mountain , quoted above, the party of picnickers gathered at the Rocking Stone, Decameron like, tell tales. The luncheon included ‘fowls, tongues, pies and tartlets’ succoured by two bottles of wine and a flask of spirit—probably brandy—'all soon disposed of', justified by ‘ the labor of conveying the said repast in baskets and parcels some five or six miles through the mountain air serving the purpose of creating that best of all sauces—a first-rate appetite.’ An experience described by the Lady Franklin’s party in 1836.

The first images (above) were stereoscopes created by Samuel Clifford in c1860. These were retrograuved for publication in newspapers a decade later. Frequently depicted as surrounded and sometimes surmounted by its sightseers, the Tasmanian photographer Neville (a close friend of Clifford) also made a stereoscope that portrayed a party of eight that included a squeeze box player. Most following photographers set the stone in its field. From some angles, the Derwent far below can be seen. The modern master Peter Dombroviskis went off-track in 1995 to immortalise the Stone by itself, framed in mist. In 2018 the Stone was used as the backdrop for craftwork.

Described as shaped like an egg or via Shakspeare—poetically belying its weight—as a cloud, some have found a canine face in it, to others it is Teddy Bear Rock (McConnell.) By 1900 its four faces were ‘studded’ with advertisements according to Launceston’s Daily Telegraph.

But why does this two ton boulder oscillate? Long before geology was thought of, Rocking stones invited speculation and around them folklore grew. Were they cradles of giants, the testing ground of fledgling witches, the judges’ bench of Druids? Supernatural powers are attributed to some rocking stones—such as the ability to cure childhood diseases and the possession of insight into the moral qualities of men.

They have always intrigued geologists. In the earliest Tasmanian explaination by a geologist named Wintle, in the Mercury of 1864: ‘The belief entertained by geologists is that it is a part of another column which, while falling, came in contact with the one that serves as a pedestal for it, and obtaining its equilibrium thereon, has retained it ever since, although exposed at times to the most terrific gales of wind.’ Wrong.

In 1866 the Tasmanian Morning Herald repeated the false explanation. In 1908 a wag in the Mercury (‘On Dit’) jestingly opined on ‘a report spread the other day that the Rocking Stone had for its axis a diamond.’ In fact, Wintle had gone on to describe the modern understanding. The Stone’s surface furnished ‘a fine example of “weathering.” The combined action of air, sunlight, and moisture have imparted to it a subglobular shape, by eating into the most exposed portions of its surface, all the angular parts being the first to disappear.’ Correct! It’s weathering that does it—the corrosive influence of thousands of years of freezing and thawing, freezing and thawing, wild winds and the chattering teeth of lichens that is the sculptor.

“Some tors are topped by rocks that have been separated from the column as a result of weathering. These perched boulders include the Rocking Stone, an elliptical rock larger than a cubic metre that is frequently moved by wind or hand without parting company with its supporting tor.”

But an explanation of the balancing act required mechanical engineers and over at least fifty years their understanding has expanded enormously as it focused on ever-smaller areas. Hungarian scientists studied the mechanics of rocking stones with 3D laser scanners to examine their contact polygons, saddle points, stable and unstable flocks, to reveal the uniform discretization of ellipses, micro-equilibria, and formalise the admissible movement component and so forth.

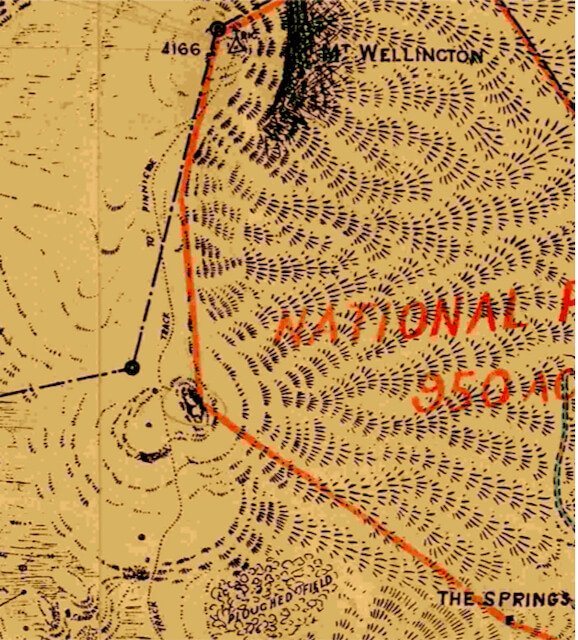

Detail: Hutchins Map showing Rocking Stone as the corner post for the ‘National Park” map overlay c1906

Despite its motion, in 1906 when the government gazetted the Mountain Park the boundary was exactly Noticed and the Park’s the south-west cornerstone was defined as The Rocking Stone.

Difficult to believe, perhaps, and granted there is no known photograph of it, but for generations, passers-by came to the Rocking Stone not just to admire it, but to use it. They came bearing walnuts for the Rocking Stone, their two ton nutcracker. They placed them under it one at a time and, by hand, made the boulder move with such millimetre precision that the shells could be cracked open without the nut inside being harmed.

Alas, for every myth-maker, there are a thousand myth busters, and around the world attempts to roll the stones aside or destroy them are deplorably frequent. The Australasian Sketcher reported in 1878—a mere decade after the Stone’s first prominence—that it had been stopped from rocking. ‘Some visitors possessing all the British tourist's capacity for mischief tried to overthrow the boulder by driving stones as wedges into the cleft portion of the base. The result of their labour was fortunately only a slight displacement of the balance of the boulder, which is now immovable'.

The rocking stone‘s immovability is contested. During the years between 1878 and 1942 some visitors report the stone immovable, others that it moved for them. The Mercury’s nature writer ‘Peregrine’ reported it still rocking in 1942. It moved for Jamie Kirkpatrick as late as 1995 and may be it will move for you, the pure of heart, for it is well known throughout the world that none with treachery in their hearts can make a rocking stone shift.

heritage VALUES

Its heritage values are natural, social (recreational), aesthetic and scientific.

SIGNIFICANCE

From PlaceNames Tasmania

To Hobart’s mountain goers, for its social value, the Rocking Stone is a feature of the mountain. McConnell and Scripps (2005) assessed it, indicatively, as of medium local significance, but with the further historical research revealing its longer, richer social history, rarity, and aesthetic appeal to and for association with important photographers Clifford, Neville, Spurling and Dombroviskis, ENSHRINE rates it as of high local significance.

It has some Tasmanian significance, recognised as an ‘interesting natural feature’ by the WPMT in its 1985 Gazeteer and also in its heritage database (WPHH0302) and for its significance to the boundary of the original Mountain Park. (Nomenclature Board PN 9346Y). In Tasmania’s Geoconservation Database it is recognised as a notable example of its type (ID 2225).

A rocking stone is a rare curiosity in Australia but it has no known national significance.

There’s a rocking stone in Victoria, several in England, many in Scotland, more again in Europe and the Americas, Asia, India, and throughout the world. No doubt there are undiscovered and emerging rockers.

The Rocking Stone may have some international significance because the mountain is perhaps the only place on earth known to have two—and close by each other: the Rocking Stone and The Little Rocking Stone.

Maria Grist at The Little Rocking Stone

NOTE

The Rocking Stone has been damaged, but it can be restored, and this has been done by the English for stones they damaged and ENSHRINE calls upon the British government to make good the damage its citizens wrought, to restore the Rocking Stone to its original functionality.

references

Cornish photo 1969b -unnumbered

Grist & Grist 2004 p7

Walking Club Map 1942

Focus on the Fringe Vol 2

NLA TROVE newspaper database

The Press (NZ) Page 1 Advertisements Column 4 PRESS, VOLUME XXI, ISSUE 2430, 20 MAY 1873, PAGE 1

The mechanics of rocking stones: equilibria on separated scales (Department of Mechanics, Materials and Structures, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Hungary)

A New Insight into the Stability of Precariously Balanced Rocks Ludmány, B., Pérez-Rey, I., Domokos, G. et al. Rock Mech Rock Eng 56, 3539–3550 (2023).