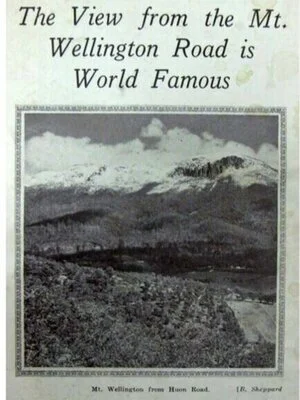

PINNACLE ROAD

“To render this lofty mountain and table land so near the city, one of the most healthful resources of pleasure and recreation unsurpassed in the world”

“A LARGE number of visitors from the neighboring colonies are now in Hobart Town, and the majority of them would not like to return to their homes without going through the feat of climbing Mount Wellington. But the ascent is so difficult that none but the hale and robust care to make the attempt. It is too great a tax upon their powers of endurance. If they could only have the road smoothed half way, it would be another matter. They would buckle to, and manage the other half. Where a road,-or, if that is dignifying it too much,-where a good travellable track can be made up the mountain side, it ought to be made. Visitors do not object to facing rough ground and steep ascents at a pinch, but they do not want it all to be pinch. ”

Tourism supremo Evelyn Emmett proposed to the premier of the day, Albert Ogilvie, a tourist road to the top of the mountain. It would be of inestimable benefit to the tourism sector, he argued—and he was right—but also, generate employment for a considerable period. Such an idea was not new.

Twenty years earlier, a visiting lecturer to Hobart in 1916, at the Royal Society, presenting lantern slide projections of Australian scenery, noted that ‘the desire for a road to the summit of Mt Wellington is not impossible of fulfilment’.

At a meeting of the Mount Wellington Improvement Association fully forty years earlier still (1870), a surveyor named Ralfe described how he had walked and measured and mapped a route to the summit, passable by carriages, so ‘to render this lofty mountain and table land so near the city, one of the most healthful resources of pleasure and recreation unsurpassed in the world’.

Laying the map of his proposed route before the committee, Balfe airily described a route from the Springs along the Mills Track, up past the old ice house, around the ploughed field (see map), through The Gap (This part, Ralfe admitted, ‘would require the aid of the crowbar and lever to remove some of the rocky boulders’) to the crest of the mountain, from whence ‘the peak is easily reached.’

‘I would advise that an avenue of one chain in breadth be cut through, the present tortuous track straightened and the timber removed to the width of only one rod right and left through the centre. The road would then be formed at once and for ever.’

To inspire construction, Balfe quoted the poet Walter Scott. To build it, he suggested the crown could employ of a gang of light sentenced offenders. To finance it, contributions could come from the Minister of Lands and Works, the Municipal Council and ‘an earnest solicitation for assistance from the upper ten hundred of the City and suburbs, and the country at large.’

The route is grossly impractical and though the track to the Falls was cleared, the rod-wide roadway to the peak was never started. Ralfe’s ‘sinews of war’ required a need far greater than any recreational pleasure. That need came during what we still call The Great Depression.

Emmet found a way that inclined from the same start point at the Springs, but went eastward. The Council and many well-off citizens contributed to a fund to employ men living on sustenance pay to build it. It was paid work for two years. The men camped higher and higher up the Mountain as they picked and shovelled and blasted their way to the top.

Suites of poems celebrated the feat. Thousands drove to the Pinnacle to witness its opening by the governor on 23 January 1937. And the Opening was broadcast on the national radio. Brass plaques memorialising the feat were installed at a new lookout. The lookout was demolished but the plaques are still up there.

HERITAGE VALUES

Historical, social and perhaps archaeological values.

HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCE

In 2018 the Park’s Trust made Pinnacle Road a priority place for nomination to the Tasmanian Heritage Register.

After years of discussion and lobbying by Madeline Ogilvy, the granddaughter of the former premier, in 2021 the Hobart City Council included ‘the Pinnacle Road reservation from Pillinger Drive/Bracken Lane intersection to summit car park’ in its Local Provisions Schedule as a historic heritage place. The nomination awaits the assent of the Tasmanian Planning Commission.

HERITAGE ASSESSMENT

McConnell assessed the road as of state significance as an important example of a 1930s Great Depression-era unemployment relief project.

Several Councillors on Hobart City Council brought the heritage value of the road to public attention and in 2024 in its new planning scheme, the Council included Pinnacle Road as a heritage place.

The road is also listed in the WPMT’s Database of historic heritage places.