pure WATER

“The numerous rivers, waterfalls and rivulets add significantly to the aesthetic qualities of the Park and to the community’s aesthetic appreciation of the Park.”

“Would that the Hon. The Minister of Works had been present, in order for me to impress upon him the necessity of granting further reserves for water supply. I feel certain that the whole of the ground must he reserved. The reservation should include not only the land, but the trees, because everything that was cut down involved an absolute loss of moisture. (Hear, hear.)”

“The rivers and the valleys, the landscapes and the river systems: they are all part of our stories.”

Waterfalls

The palawa have many words for different states of water and the mountain’s lower waterfalls would have been well-known and visited on hot days. They also, potentially, became refuges in calamitous bushfires. “The rivers and the valleys, the landscapes and the river systems: they are all part of our stories,” says Sharnie Read, the TAC Aboriginal Heritage Officer.

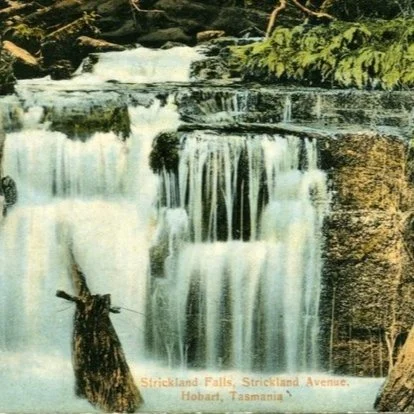

Adventurous early Hobartians could wade up Hobart Rivulet almost to the foot of the Organ Pipes, passing several waterfalls, but the first period of mountain waterfall appreciation commenced in the 1840s with the public adoration of Wellington Falls—“The Falls” on the mountain. A second gush of appreciation came in the 1880s, Another burst in the 1930s with waterfall postcards proliferating, some hand-tinted, out of the developing tanks of John Beattie’s photographic studio. This appreciation encouraged the building of tracks to the best known / closest falls.

Yet after a century, the Hodgman map of 1936 marks only four: O’Grady’s, Featherstone Cascades, New Town and Gentle Annie. Today, the mountain’s water lovers extoll more than a dozen easily approached tumbling vistas, several with scenic admiration bridges.

Pure Drinking Water

The drinking water catchments within Wellington Park provide 20% of greater Hobart’s drinking water.

HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCE

Waterfalls cultural value is aesthetic and social. Waterfalls were one of the key attractors for track-making, hut-building and mountain visiting. Wellington Park Management Trust has given several of these waterfalls heritage code recognition (i.e. a HH number.) Several Wellington Park falls appear on top-10 lists of Tasmanian waterfalls.