BEAUTEOUS LANDSCAPES

“The natural beauty of Mount Wellington was always Hobart’s greatest attraction.”

Only two Acts of Tasmania’s parliament use the word beauty. Excluding the Beauty Point Landslip Act, one is the National Trust Act, the other the Wellington Park Act but only the latter has the word twice. Beauty is not just in the Wellington Park Act: it empowers it and the park’s trustees. Beauty—its preservation and protection— is one of the five cardinal purposes of the Act.

“The park is reserved for the purpose of the preservation or protection of the natural beauty of the land or of any features of the land of natural beauty or scenic interest.”

That the park contains natural beauty is explicit but by itself alone the lofty Purpose of the clause is merely aspirational; without a working formulae showing how to identify its beauty we cannot say where it is upon the land, strategically is obscured and management … let Will it fulfil the purpose?

What is and where is the natural beauty of the land in the Park?

The Act is empty. There is no map. The meaning and limits of ‘natural beauty’ or ‘feature’ or ‘land’ are not defined nor were they debated during its enactment. This dearth tempted both of Tasmania’s practitioners working in this field to take deep dives into aesthetic theory, and we will quote them to show the development of the mountain as a beauty, and also because the management plan transfigured beauty into a Visual Sensitivity 3-colour, 2D printed map 12 in the management plan. but up-front: nothing fancy is required, it is a theory-free zone where what is meant is the ordinary meaning of the words. Policy-makers need only consult the English Dictionary.

We did, but as well, we intend to be strict and tight in our application. We start on land because only land matters. Land is not sky nor its falling waters. A landscape is not land. Land is not any living thing—however beautiful. Land is the solid and immovable part of the earth itself. ‘We confider rocks and mountains as part of the earth itfelf’ wrote the Picturesque stylist William Gilpin centuries ago. It is the unadorned beauty of the hills and mountains themselves, no more that is to be preserved.

What of natural beauty? In the dictionary natural beauty is the beauty of nature itself, but stop! We needn’t define nature because we are dealing only on land. Beauty!

Beauty is as old as Latin’s bellus. It is that quality that gives pleasure to the mind by the intervention of the senses; it is any of the qualities of the land that delight the eye, the ear or the mind, but there are many limitations. Not all nature is beautiful, much of it is beautiless, and the Act’s framers recognise this because their second use of the word beauty adds to the list of protected species, so to speak, [individual] features of natural beauty. Alongside that, the clause protects land with scenic interest. Features of the land possessing natural beauty obtain the same protection, notwithstanding that they may reside in beautiless places. Beauty has no scale, its features may be as small as a pond, as vast as a mountainous range and natural beauty is not only visual, it may be aural, it must be mental. But it can’t be smelt or touched. While the look or sound or even the description of falling water may be beautiful; neither its pure taste nor its cool deliciousness can be (explicitly) described as beautiful. Strictly, features described as handsome may not be beautiful.

[As an aside, ‘scenic interest’ is also not considered below. It is considered here.]

Historic beauty

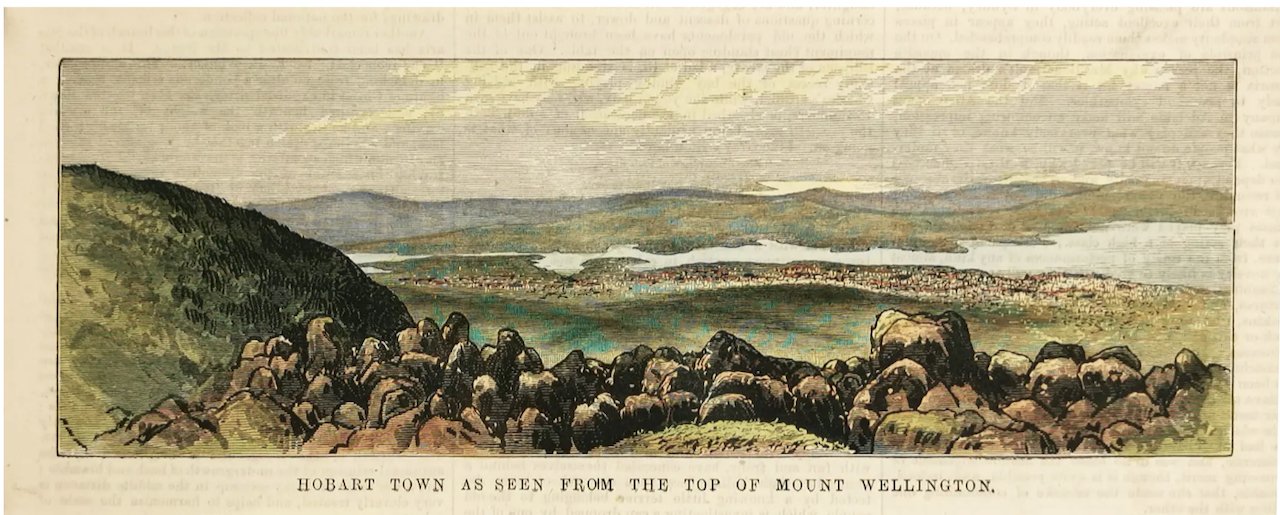

The mountain’s beauty has been extolled in literature and journal from the time of settlement. Sheridan found the word ‘liberally sprinkled throughout the vast array of literature’ she consulted. In the pages of the Tasmanian press over three centuries, it is not unusual to have the mountain’s pinnnacle conceitedly described as possessing the most beautiful view on Earth.

Beauty + Mount Wellington Trove search results

The interest in beauty waxes and wanes, but note that Trove results past 1954 are so sparse they cannot be relied upon to suggest that beauty has waned.

A quick (and dirty) Boolean term search of Trove’s newspaper database for the phrase “Mount Wellington” + “beauty” finds 11,000 results.

The results by state and by decade are screenshot.

Remove advertisements and the hits halve. (But here is one advertisement: ‘At the back is commanded a fine view of our lofty Mount Wellington, whose Wild grandeur as a background object in the scenery cannot be surpassed’ (Tasmanian Times 7/1/1870). To this day, in Hobart real estate listings, even a glimpse of the mountain from within the property boundary rarely goes without notice and a demonstrative image.)

1820-

The earliest beautiful description is April Fools Day, 1828 under the headline The Weather. ‘On the 21st ultimo, Mount Wellington presented a most beautiful appearance, being entirely covered with snow, which still remains.’

Another. ‘Sydney Town wants that picturesque appearance, as to situation, which the capital of Van Diemen’s Land enjoys in an eminent degree. There is no Mount Wellington in Sydney, throwing its awful background to the town.’— The Australian (Sydney) 18/7/1828

‘It was a beautiful, clear morning - the mist that at early dawn, had been overhanging the summit of Mount Wellington, had gradually disappeared, exhibiting its rough and towering majesty in all its splendour…’ Colonial Times 30/10/1829.

1830–

This Mountain stands about four miles from Hobart, (bird's flight) but in the evening at dusk in a particular state of the atmosphere, it appears to overhang the town, and has then a sublime appearance.’ The Tasmanian 17/1/1834

1840–

‘… a tract visible to the naked eye 140 miles in diameter, forming a panorama which, for beauty and diversity of scenery, we believe is not to be surpassed in the world.’ Courier 22/4/1845

‘Mount Wellington, in towering majesty, bounds the City westward ; - sublimely raising his snow-crowned brow, frequently above the clouds, which roll in grandeur beneath his feet.’ Hobarton Guardian 28 August 1847

‘For the beauty of the landscape, the inhabitants of this island were peculiarly favoured—and the lecturer [Bicheno] referred to the view of Mount Wellington—the glorious mountain.’ Courier 20 June 1849

1850–

Who can look on the sublimity of that magnificent mountain that towers above them (Mount Wellington) with its varying veil of mist…without sensible delight?’ The Britania 21 June 1851

1870–

'Mount Wellington overhung the city in all his primeval and barbarous beauty.’ — Marcus Clarke The Settler in Tasmania 50 years Ago from “Old Stories Retold” The Australasian 2 July 1870.

1890–

‘When the sun is shining brightly it pierces here and there through the dusky foliage, so that the chequered light and shade and the alternation of green and gold colours produced are lovely to look upon.’ E.P.D. Mercury in January 1899.

1910–

‘I have climbed mountains in four States, and in my memory have something of a collection of inspiring views, but nowhere do I know of a panorama so fairy-like and enchanting as the wide vista which with lightning change and almost bewilderingly varied beauty evolves itself to the right seeker who ventures to the rock-strewn cap of this silent sentinel of Southern Tasmania.’ P. de Crespigny, Mercury, 14 Sep, 1912

1930–

‘This beauty seems to be more than earthly, in the reaction of the mountain to the light of dawn and the splendour of the sunrise; or when the mountain appears to float in blue sea-haze, or responds to the interplay of light and cloud; or when, to the pale sun, its snows are dazzling white in contrast with the blackness of the immensity of its base; or when the height looms wine-dark against the sunset. It is grim and forbidding only in the darkest moods of storm. Its magnificence is changeless; its beauty moves with the pageant of the seasons.’ Roy Bridges, Melbourne Argus 1931.

Beauty is not eternal, but these quotations strongly suggest that the conception of the mountain’s natural beauty is not only long-standing—it arises very early—but remains remarkably durable. Some beautiful spots have since been robbed of their beauty: Sheridan notes the loss of the dense Dicksonia antarctica undercover in the broad gullies as a notable loss to the historic landscape values. A handful of places have recently emerged as beautiful, but only a few once-thought beautiful places have fallen from favour. .

Painterly beauty

Artworks do not make the mountain beautiful, but they are, Angela McGowan says “strong evidence that it is viewed as beautiful.” Sheridan presumed that ‘most of the painters wanted their viewers to take away a particular perception of the mountain and beauty was an integral part of it.’ Paintings are useful in delineating the landscapes and features that both the artist and the purchaser likely consider possess natural beauty.

As with the written praise, painterly attention began immediately and has hardly ceased. Every colonial-era painter of stature painted the mountain and it is as popular with artists today who create entire shows devoted to it. Ditto photographers. [At Aesthetic Landscapes over 200 paintings are collected.] Typically, artists produce works they believe the public will be interested in seeing and purchasing. The price that the artworks command and the importance of the collectors who buy them are evidence of significance.

Elements of/in nature said to make landscape paintings beautiful include ‘the nourishing and exciting of curiosity was a key pattern. The achievement of landscape harmony which encompassed an overall blending into a unified whole was a goal as was a rich diversity of form. Other signifiers were softness, graduated colours, light and shade, delicacy, order, symmetry, appropriation and animation, simplicity and muted gentle responses to landscape, some of these creating the perception of a ‘feminine’ beautiful. The Picturesque allowed entry of a certain roughness and irregularity, surprise and novelty, contrast, continuity and association. Long distant prospect views using subtle depth of field techniques came into being and the sky, (in art work) became integral to an entire landscape picture.’ (Sheridan V2 p 60)

Officially beautiful

References to and recognition of the parkland's natural beauty appear throughout the Park’s management plan.

‘Wellington Park…is an area of outstanding natural beauty’ (p 15). ‘The visual beauty of Wellington Park is one of the most important factors shaping people’s perception of it’ (p 24). ‘the broader Wellington Range [has] highly significant visual value’ (p 81).

More frequent in the plan, however, are references to the broader concept of aesthetics. Aesthetic qualities, aesthetic values, aesthetic characteristics.

For example:

‘The geology, striking landform, cultural history, running waters and diverse vegetation, and temporal changes of lighting, climate and atmospheric effects all contribute to the Park’s outstanding aesthetic characteristics’ (p17).

‘Its setting, height, shape, geology, striking landforms, steep altitudinal cline … all contribute to its aesthetic beauty’ (p 80).

The Management Plan may discourse on anything it considers aesthetic, but much of what it cites: cultural history, running waters, diverse vegetation and atmospheric effects, cannot be protected by Clause 5 because none of these attributes or characteristics or features are ‘of the land’. The management plan may be deliberately distinguishing the Park’s aesthetic values from its beauty, but the Act is only concerned with beauty. The management plan makes a distinction between the ‘natural landscape’ and the ‘aesthetic landscape’ (see page 82) but no landscape and only the aesthetic quality of natural beauty of the land is covered. The Sublime is not covered by the Act nor mentioned in the management plan.

Beautiful Features

In the management plan references to the beauty of natural features, too, are frequent.

The mountain’s ‘earth systems’: its waterfalls, cliffs, gullies, rocks and viewpoints, are recognised, simultaneously, as the ‘foundation for the Park's ecosystems’ and ‘the basis for its high landscape value’.

The plan refers to the land’s ‘striking landforms’, ‘outstanding topographic landmarks’ and ‘prominent geological features’: such as ‘the toppling dolerite columns along its eastern escarpment’; in combination with its ‘variety of smaller landscapes’, for example the high-altitude, periglacial landforms, the dolerite boulder streams and boulder fields that ‘provide much of the landscape character of the higher parts of the Park’ (p 74). These are all natural features of the land (likely) naturally beautiful.

Certain specifically beautiful features are named. ‘Prominent’ geological features named in connection with ‘the landscape character of the Park’ are: Sleeping Beauty / Collins Cap, Collins Bonnet and the Organ Pipes, (p17 and 74), Lost World, the Yellow Cliffs, the ‘spectacular’ Organ Pipes, and the ‘large, perched boulder known as the Rocking Stone’ (p 20).

Some of the natural features the management plan lists as aesthetically significant must, alas, be struck. The park’s ‘running waters’ and in its ‘wildness’ (p 24), its ‘continuously and diversely vegetated slopes’ (p24), its darkness, where ‘cultural history contributes to [the Park’s] aesthetic beauty’, the ‘very unusual’ Disappearing Tarn, the ‘aesthetically outstanding’ Silver Falls (p 226) and the effect of a foreboding, obscuring cloudscape of storm and mist across the diversely vegetated slopes (i.e. atmospheric effects generally) are none of them features of the land.

Beautification

Can natural beauty be improved upon by humans? Perhaps, but the Act will not protect any beauty that is not natural. The mountain’s beauty spots cannot be protected by this part of Clause 5. Though composed of stone or wood, the ‘spots’ are made by us and built beauty is not natural nor is it ‘of the land’.

Beauty Treatment

Aware and alive to its responsibility for the preservation and protection of the mountain’s natural beauty, the trustees commissioned two major reports into beauty. The first was a 5-volume enquiry by Gwenda Sheridan into The Historic Landscapes Values of Mount Wellington. The second was Wellington Park Landscape and Visual Character and Quality Assessment by Bruce Chetwin. The former report is quoted but its historic and aesthetic mapping was not referenced. The latter report formed the basis for visual sensitivity zone mapping.

Beautydom

In response to this reporting, the management plan contains a map (commissioned for the Plan) that clothes beauty with three coats of visual sensitivity, grading the land as of low, medium or high visual sensitivity. The map does not identify specific natural features. Only the obvious link between sensitivity and altitude is shown. The map’s application is thus of more relevance (if it is not restricted) to scenic interest rather than natural beauty.

High Scenic Quality map of Wellington Park. The beauty blobs are frequently over prominent (i.e high) points such as mountain peaks (Table Mountain, Cathedral Rock, The Organ Pipes, Collins Cap) but also includes Wellington Falls and ferny gullies on the lower eastern slopes. Visual Management Sensitivity plot. WPMP page 84

Panoramas that create the aesthetic effect of the Sublime

Gwenda Sheridan’s Landscape study 2010

Beauty Management

With the Park’s natural beauty revealed, the question turns to how the trustees can preserve or protect it.

The Plan has a Landscape/Aesthetic Values management policy. It proposes (at page 82) to include established aesthetic values and landscape characteristics in its GIS, to distribute its Historic Landscape Values report to all relevant land managers so they can do the same and requires a Visual Impact Analysis before any decisions about major works or developments is made—a kind of Potential Beauty Impact Statement is required. Sounds good, but the aforementioned statements on aesthetics, spread throughout the management plan, as well as the policy actions referenced directly above do not oblige a developer or user. Legal consequence stems only from what is contained in the Park’s Planning Scheme in Chapter 8.

The first step, nevertheless, is to find the natural beauty, then list it in a Register of Beauty. The Trust has such a register in the form of its Historic Heritage database and it contains over 50 natural features. The features range from mountains and hills to boulder fields, caves and individual stones; water features listed include tarns, springs and waterfalls; there are also glades and even singular trees inscribed.

The trustees have forewarned on page 8 of their 2024 Annual Report that they are considering removing all natural features from the database on the basis that they are ‘afforded alternative protection under the Wellington Park Act 1993’. Which clause in the Act offers the ‘alternative protection’ is not stated. We do wonder. The report continues, ‘Given the potential application of the Heritage Database in constraining use and development in Wellington Park, rigour is paramount.’ Presuming a protective clause exists, and it is as equally effective, how would removing the features from the database change the constraint on use or proposed developments?

Expulsion would contradict the plan’s commitment to aesthetic values as ‘a fundamental value’ (p 82), and more importantly, to remove them may constitute a failure to comply with the Act’s purposes, but the ground truth is that proposed developments are dealt with by the planning scheme provisions in the management plan, in Chapter 8, not in the clauses of the Act.

The Beauty Plan

In the first sentence of Chapter 8, it is written: ‘Wellington Park is highly valued by Hobartians and the wider Tasmanian community for its natural beauty’, and the following General Assessment Requirement for all ‘proposals for activities, use and development’ is that they are ‘required’ to ‘demonstrate’ that they will not ‘diminish’ the Park’s natural or aesthetic values (p 134). This requirement is also mirrored in the LUPPA Assessment process at WPMP on page 138. Having said that, the management plan then makes a significant exception when it distinguishes between a compromising/diminishing disturbance of the aesthetic or natural landscape values ‘when viewed from outside the Park’ as against that within. Again, this is of most impact on scenic interest. [Regrettably, scenic interest is not an Issue with performance standards.]

The test of whether a proposal meets the Requirement is determined in the standard for Landscape, visual quality and amenity. (page 146, 158 and again at 173). The Objective is ‘to protect and enhance the landscape and visual quality of Wellington Park.’ Wait! The word enhance appears to have sprung from nowhere. How can—even should—natural beauty be enhanced?

The Acceptable Solution is for any proposed buildings and structures to be outside the areas identified (see map 4) as High or Moderate Visual Sensitivity.

The performance criteria is clear: ‘Buildings and structures in prominent locations visible from within or outside of the Park, or identified as of High or Moderate Visual Sensitivity in Map 4 of this Management Plan, must be designed and sited to minimise or remedy any loss of visual values or adverse impacts on the visual character of the affected area.’

To a lesser extent, the standard for Building Design protects (rather than preserves) visual beauty by, ideally, restricting the size of buildings to that of a 1-storey, medium-size house (floor area of less than 100 sq metres) that ‘do not cause visual intrusion’. That criteria is manifestly inadequate.

In 2022 came a proposal for a building in a High Visual Sensitivity area that was on seven-levels, had a floor area of over 2000 sq metres, and was at one place fourteen metres high. Clearly without an acceptable solution, the proponent argued that the building met the performance criteria because it was designed and sited to minimise any loss of visual values, and harmonised with the site. The Planning Authority rejected this argument and its decision was upheld on appeal, but how could such a large-scale development be even contemplated?

All that is covered by the Act may be only a fraction of the Park’s beauty, but what is crucial is that that which is covered is covered absolutely and forever and without exceptions. The beauty of the land is inviolable. And here’s why. It's because of another word—the most important word in the entire Act: reserved. The Park is reserved. Reserved for certain purposes. Certain purposes and no other purposes. Because the land is beautiful it is reserved. Because it is reserved all its natural beauty must be preserved or, if that is impossible, protected. The natural beauty of the land cannot be removed, altered, damaged, built over, covered. Any work that alters the land is not permitted by this clause. Building is out.

As the Act does not use the word aesthetics, these chunks of the management that rely upon its aesthetic judgement may be ruled illegal, reducing the plan to platitudes, nothing more than an aesthetic opinion.

it appears to us, is not adequately protected by the current management plan.

The state’s Cultural Heritage Act, by contrast, specifically protects places exhibiting ‘particular aesthetic characteristics’, and so does the national heritage register.

HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCE

The Wellington Range appears on the first map of the area, by Hayes, in 1798.

The Beauty Spots have been captured by artists, poets and writers ever since.

Tracks have been built to reach beauty spots, and shelters and lookouts built beside them.

Regal inspection Queen Elizabeth II inspects the mountain in 1954. Whilst visiting Cape Town, South Africa in the early 1960s and taking in the view from Table Mountain, the Queen reportedly told palace staff it was not as beautiful as Mount Wellington and the view over Hobart. The Advocate newspaper 29 May 1989

The View of the Mountain’s landscape has not displeased the only humans who can be mentioned in connection with nobility and majesty. Royalty.

During the visit to Tasmania in 1900 by the then Duke and Duchess of York, hence England’s King and Queen, a Mr Knight, reporting for London’s Morning Post wrote that from the deck of the royal ship chartered for the cruise: “We had seen in Australasia a succession of the finest harbours in the world. It would be difficult to pick between them, but as far as the aspect of a city as seen from the sea is concerned, I think that Hobart must take the palm; behind the picturesque city covering the lower foothills stands a grandly shaped mountain, its slopes covered with dense forest from near the summit to the foot of a precipice of dark, rocky pillars, like the pipes of a gigantic organ. Truly Mount Wellington forms as noble a background to a city as can be found in the world.” So impressed was Hobart’s Mercury, it republished the comment thirty years later—and ENSHRINE can’t resist either. Does this give the view international significance? Certainly, this pair were not the only or the last Royals to be impressed, as Tasmania’s Advocate newspaper reported: ‘Whilst visiting Cape Town in the early 1960s and taking in the view from Table Mountain, the Queen of England reportedly told her palace staff that it was not as beautiful as Mount Wellington and the view over Hobart.’ (Advocate 29 May 1989)

An additional cultural significance is attributable to the mountain at night. It is a place popular for aurora-seekers, but its dark beauty has been significant to indigenous Tasmanians too.

Their importance is so great (as noted above) their ‘preservation or protection’ is one of the four key purposes of the Wellington Park Act 1993. This legislative purpose finds expression at the heart of the management plan in statements such as this: ‘The visual beauty of Wellington Park is one of the most important factors shaping people’s perception of it’ (WPMP page 24).

A few places have been beautified, and the courses of tracks have been turned to pass beauty spots; indeed, some of the walking tracks were built in order to allow admiration them. Bench seats and lookout platforms and sometimes shelters have been constructed to extend the ease of enjoyment. Subsequently, by frequent depiction in literature, upon canvas, and on waterproof map; and, by being protected by law and custom: the con-fusion is deepened.

HERITAGE ASSESSMENT

“The Mountain has historic cultural heritage significance ... for its potential to contribute to the understanding of important aspects of Hobart’s heritage including:

(iv) Aesthetic characteristics. The scenic grandeur of the mountain is demonstrated across two centuries of artistic representations by many notable 19th and 20th century artists and photographers, with the mountain featured as a primary element.”

A 208 Network report to the Wellington Park Management Trust concluded that the views of Mount Wellington from the City of Hobart ‘have or possibly have National Estate value for their scenic qualities alone.’ A statement cited in McConnell and Handsjuk’s WPMT’s 2010 Summit Area Heritage Assessment.

Only the National Trust Act (not the National Parks Act) contain the word beauty.

That the Park has visual beauty is stated in the management plan (page 81).

The Glenorchy, Kingborough and (soon) Hobart Planning Schemes all contain an overlay of their portion of the mountain park protected a Scenic Protection Area.

‘The highly significant visual value placed on the broader Wellington Range, is directly attributable to the scale and prominence of the Range and its features and to the integrity of its ecosystems (McConnell, 2012)’ (p 81).

In terms of recognition, the finest (and perhaps those most at risk) examples should be recognised first. Is the mountain Hobart, Tasmania or Australia’s most beautiful mountain? Yes, to Hobart but probably No to the latter.

Comparative Appraisal

“There is considerable divergence of opinion, by the way, as to the respective merits of the mountain view and that at the Gorge at Launceston.”

Against the terrific splendour of admiration, no art critics argue that the mountain is ugly. But there are degrees of beauty and a comparative assessment must ultimately be made. A few argue that the mountain is (relative to them) not much of a mountain or that other peaks are more beautiful.

In a lecture on Art and Ugliness read by a Dr Mercer (reported in the Daily Telegraph Launceston 17 Aug 1905), the doctor opined on beauty and concluded that “the finest mountain in Tasmania was not Mount Wellington, as perhaps they thought he should say, but Mount Roland”, and he descanted at some length on the particular beauties of this 'grand old feller.' In his survey of the work of de Wesselow, the Hobart artist Max Angus wrote ‘Its features and general appearance are therefore better known than some other Tasmanian mountains which possess a more dramatic or spectacular form.’ Neither judgement goes so far as to say that the mountain is not naturally beautiful. Even when the author and critic Peter Conrad in 1988’s Down Home: Revisiting Tasmania famously anthropomorphised the mountain as ‘a brutal and bad-tempered eminence' that ‘grimaces, squeezes the settlement’, and saying the mountain ‘invigilates every back yard’ he is expressing the mountain’s terrible—sublime—beauty.

None of this critique denies the long-standing and widely held judgement of the mountain as a beautiful place. The issue is that in terms of state and national recognition, it must be the acme, or at least amongst, the most beautiful.

HERITAGE VALUES

Beauty Spots exhibit Historic, Indigenous, Aesthetic, Scientific and Social heritage values.

LOCAL HERITAGE

Tasmania’s local planning scheme does not have a zoning or even an overlay for beauty or beauty spots, but it does recognise what the Act’s Purposes include as ‘scenic interest’. Preserving or protecting the mountain’s beauty at the local level is achieved by including a Scenic Protection Area overlay in each relevant Council’s Local Provisions Schedule. Kingborough and Glenorchy have complied. A SPA is under consideration in Hobart. See our nominations here.

STATE HERITAGE

“Wellington Park [is] an area of outstanding natural beauty.”

The mountain stands an excellent chance of being inscribed into the state’s heritage register.

Tasmania’s Heritage Council may recognise a place in its Heritage Register for its beauty. The Act provides for an aesthetics criteria. Criteria (h): ‘importance in exhibiting particular aesthetic characteristics’ [Clause 16, Historic Cultural Heritage Act 1995].

By applying an aesthetic test, the Heritage Council can recognise places likely not admissible within the Wellington Park Act’s recognition framework which is restricted to beauty.

In a Statement of Significance prepared by Gwenda Sheridan in 2010 for the Wellington Park Management Trust, addressing the state’s Cultural Heritage Act criteria (e)—because in 2010 the aesthetic criteria did not exist—she concluded:

‘Aesthetic values lie at the heart of the Mount Wellington-Wellington Range and foothills area landscapes. Mount Wellington embodied in its landscape, aspects of the Sublime and the Picturesque demonstrated through a significant archive of colonial artworks particularly of the nineteenth century. It signifies wholeness and beauty (important aesthetics considerations) and it is the combination of the landforms and vegetation patterns, weather conditions, and aggregated cultural elements which give rise to this. These have resulted in significant and at times profound textural, colour, form, structure and line contrasts, immense variety, diversity, light and shade, order, symmetry, novelty, sometimes irregularity and roughness, grandeur, and other elements which were considered key landscape determinants in the past. For Mount Wellington it is the unique way in which these principles and key determinants are aggregated together into a unified ‘whole’ which gives the mountain its strength of aesthetic appeal. This can occur at a broad general level or on a localised, individualised smaller site level.

The mountain’s aesthetics appeal was innately recognised by colonial and later artists who attempted to commit the aesthetics of the mountain to canvas. The snow cover which used to lie on the upper slopes of Mount Wellington for many months of the year had particular appeal; this introduced quite a different set of aesthetic forms to perception of the mountain mass. Snow enables a soft light, a more muted gentle response to the landscape, a delicacy to some of the forms that were /are seen and experienced (e.g. tree ferns with a snow cover). Frost similarly affords different aesthetic responses. Mount Wellington is also able to demonstrate that it contains wild and wilderness values. The landscape aesthetics are a part of this and add significantly to it. These values are most important because of their relative manifested proximity to Hobart. Wildness and wilderness is present in that this mountain mass joins contiguously with the World Heritage Area and South West Tasmania. Enclosed rainforests, wet forests, the high open plateau contain wild and remote values. Even parts of the eastern face contain wild and 'remote' feeling values. Such values are mainly due to vegetation and landform patterns and lack of perceived development of any kind.’

Sheridan is a suitably qualified person to make this assessment.

The extensive references to the mountain’s aesthetic significance in the Wellington Park management plan quoted above are also highly suggestive of the view that the mountain exhibits particular aesthetic characteristics.

The purchase by significant public art galleries of images of the mountain is indicative of the aesthetic significance of the object portrayed. Galleries with important images of the mountain include The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, The National Gallery, Canberra, The National Galley of Victoria and the Art Gallery of NSW. A significant painting is also possessed by the National Library of New Zealand.

NATIONAL HERITAGE

“Mount Wellington-Wellington Range is significant as a forest place of aesthetic value, important to a community for aesthetic characteristics held in high esteem or otherwise valued by the community. The Wellington Range is valued for its dramatic cliffs which evoke a strong sense of awe. The Range and Mount Wellington in particular is a major part of the landscape and scenic character of Hobart and the Derwent estuary, acting as a counterpoint to the built environment.”

In the Park’s management plan’s Statement of Significance, under the title Beauty, Landscape and Sense of Place it is written: ‘Mount Wellington is … important to all Australians as a visual reference point for much of southeast Tasmania and the signature landmark for the city of Hobart. The area’s natural and landscape significance is heightened by its close proximity to a capital city, a feature unique in Australia’. The plan also comments: ‘While most Australian capital cities are located near the coast on rivers or harbours, Hobart is unique as the only capital city with an inspiring mountainous backdrop close to the city (p16–17).

The plan considers ‘preparing an application for National Heritage Listing for the Park, based upon the Park’s identified … landscape … values’ (p 82).