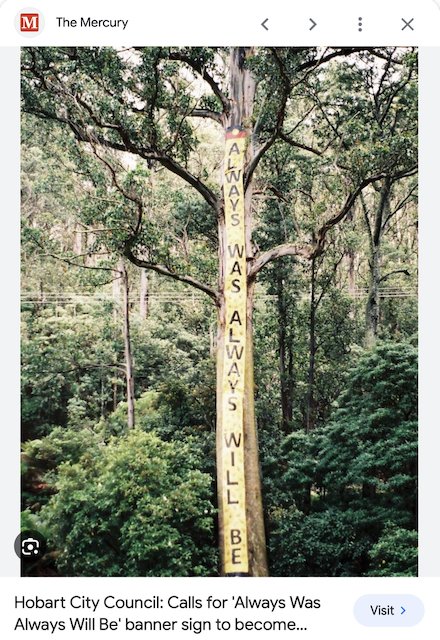

Aboriginal Sovereignty

“takamuna rrala kunanyi-ta! takamuna rrala kunanyi-ta!”

Sainty translated her own chant as: “We will fight to keep the spirit of kunanyi, our mountain, strong!”

Aboriginal Tasmanians, pointing out that they never ceded their land, claim that the mountain is theirs, and seek to regain ownership of it. The Park was a prominent landmark throughout Southern Tasmania. Pallawa and Pakana were known to travel great distances and it is possible the mountain was widely known. But even if it was not, many Aboriginal people now live in Hobart, and culture is a process that always evolves.

Against this ambition, it has been argued that any such transfer lacks grounds. The traditional owners were the Muwinina, but they have no known descendants. So what right do other, unrelated Aboriginal people with no traditional association to it, have? Also, the Park has always been known colloquially as the People’s Park. And it belongs to everyone.

When tasked with exploring a treaty, during a 2021 fact-finding mission by two legal academics, professors Kate Warner and Tim McCormack, the Aboriginal community expressed an especial ‘interest in kunanyi being returned to the Aboriginal people’. (The other area specified was in the Great Western Tiers.)

Their legal options report Pathway to Treaty and truth-telling noted that for many Tasmanian Aboriginal people ‘kunanyi is a special place that features in creation stories passed down through generations, and it is a sacred place where ancestors’ spirits are laid to rest.’ Sharnie Read, a pakana and Aboriginal heritage officer expanded on this: “It’s a pathway to our ancestors and to the spirit world, a doorway if you like to the next stage of who we are.”

The Lord Mayor of Hobart, Councillor Anna Reynolds was also consulted. She supported the concept, suggesting “adding an Aboriginal overlay to kunanyi, or joint management with Aboriginal people of Wellington Park.” A footnote states that some understood ‘this would not be possible unless the land was first returned to Traditional Owners’ but the authors explored two legal pathways—via the existing Nature Conservation Act or through a new Act—by which this could be achieved.

Pathway to Treaty and truth-telling recommended:

13. Consider creation of kunanyi / Mt Wellington an Aboriginal Protected Area

‘We recommend that the Government seriously explore the possibility of this using the recommended statutory framework for Aboriginal Protected Areas.’ Note: the concept of an Aboriginal Protected Area does not currently exist in Tasmanian law.

In a further recommendation, ‘one option for helping supporting the land management functions of Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania is the possibility of using park fees from kunanyi to fund the management of lands returned to the Aboriginal people.’

Against this, there are no Park fees charged and imposing them would be controversial. Moreover, the expense of collecting such fees may prove almost as costly as the revenue they raise.

In 2023 the Wellington Park Management Trust engaged 35 Pallawa and Pakana senior knowledge holders to advise the Trust.

In 2024 the former Governor of Tasmania, the law professor Kate Warner again argued for the Aboriginal Protected Area after the state government announced a call for ideas as part of its high-level strategic review of Mount Wellington. She noted in an interview that having been handed-back, as in many other places, the land would then be leased to, say a local or state authority for an annual fee. The reservation thus achieving both a financial and a restorative outcome.

Against this, the Park is said to be grossly underfunded at present. Essential services are in advanced stages of decay and are over-extended and no one wants to pay for replacements. The hand-back on the terms above would create another mouth to feed, and what else?

ENSHRINE argues for the recognition of Aboriginal history and culture in the Park and its protection and its interpretation. Moreover, our concern is not who owns the land or who manages it, but how all its cultural assets are recognised, preserved or protected. Having said that, an Aboriginal Protected Area (or ownership) might be unique and would in either case greatly enrich the cultural story of the mountain.

Therese Sainty

An alternative legal status and tenure for the mountain as a legal person (much like a corporation) has also been raised. This legal status has been created in Aotearoa/New Zealand for Te Urewera and Mutehekau Shipu in Canada. This status would give the mountain legal standing in a court to defend and protect its features and itself.